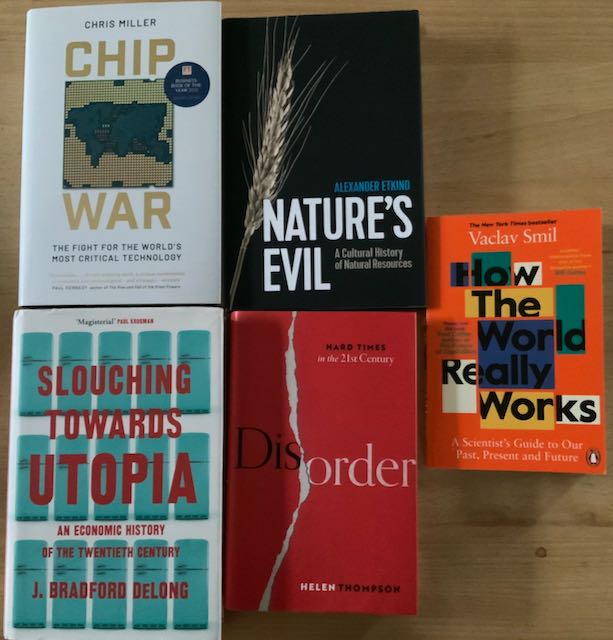

2022 was a completely dismaying year; here are a few of the books I have actually checked out that have actually assisted me (I hope) to put in 2015’s world occasions in some type of context.

Helen Thompson might not have actually been luckier– or, maybe, more farsighted– in the timing of her book’s release. Condition: difficult times in the 21st century is a study of the continuing impact of nonrenewable fuel source energy on geopolitics, so could not be more prompt, provided the effect of Russia’s intrusion of Ukraine on gas and oil products to Western Europe and beyond. The value of protecting nationwide energy products goes through history of the world in the 20th century in both peace and war; we continue to see examples of the deeply grubby political entanglements the requirement for oil has actually drawn Western powers into. All this, by the method, offers a strong secondary argument, beyond environment modification, for speeding up the shift to low carbon energy sources.

The existence of big reserves of oil in a nation isn’t an unmixed true blessing– we’re growing more knowledgeable about the concept of a “resource curse”, blighting both the politics and long term financial potential customers of nations whose economies depend upon making use of natural deposits. Alexander Etkind’s book Natures Evil: a cultural history of natural deposits is a deep history of how the products we depend on shape political economies. It has a Eurasian point of view that is really prompt, however less familiar to me, and takes the concept of a resource curse much even more back in time, covering furs and peat along with the more familiar story of oil.

With more attention beginning to concentrate on the world’s other possible geopolitical flashpoint– the Taiwan Straits– Chris Miller’s Chip War: the defend the world’s most crucial innovation— is an excellent description of why Taiwan, through the semiconductor business TSMC, became so main to the world’s economy. This book– which has actually appropriately won radiant evaluations– is a history of the common chip– the silicon incorporated circuits that comprise the memory and microprocessor chips at the heart of computer systems, cellphones– and, significantly, all type of other long lasting products, consisting of automobiles. The focus of the book is on organization history, however it does not avoid the essential technical information– the production procedures and the tools that allow them, significantly the advancement of severe UV lithography and the increase of the Dutch business ASML. Outstanding though the book is, its organization focus did make me show that (as far as I know) there’s a substantial space in the market for a popular science book discussing how these exceptional innovations all work– and maybe hypothesizing on what may follow.

Slumping Over to Paradise: a financial history of the 20th century, by Brad DeLong, is an elegy for a duration of unrivaled technological advance and financial development that appears, in the last years, to have actually pertained to an end. For DeLong, it was the advancement of the commercial R&D lab towards completion of the 19th century that introduced a long century, from 1870-2010, of unrivaled development in product success. The focus is on political economy, instead of the product and technological basis of development (for the latter, Vaclav Smil’s set of books Producing the Twentieth Century and Changing the Twentieth Century are important). However there is a welcome concentrate on the product substrate of details and interaction innovation instead of the more noticeable world of software application (on the other hand, for instance, to Robert Gordon’s book The Fluctuate of American Development, which I examined rather seriously here).

Though I am really considerate to much of the arguments in the book, eventually it left me rather dissatisfied. Having appropriately worried the value of commercial R&D as the motorist of the technological modification, this style was not truly highly established, with little conversation of the altering institutional landscape of development around the globe. I likewise want the book had a more strenuous editor– the prose lapses on event into debauchery and the book would have been much better had it been a 3rd much shorter.

On the other hand, Vaclav Smil’s most current book– How the World Actually Functions: A Researcher’s Guide to Our Past, Present and Future— plainly had an exceptional editor. It’s an extremely engaging summary of a number of years of Smil’s respected output. It’s not a boast about my own knowing to state that I understood practically whatever in this book prior to I read it; merely a repercussion of having actually checked out many of Smil’s previous, more scholastic books. The core of Smil’s argument is to tension, through metrology, just how much we depend upon nonrenewable fuel sources, for energy, for food (through the Haber-Bosch procedure), and for the raw materials that underlie our world– ammonia, plastics, concrete and steel. These chapters are excellent, strong, data-heavy and concise, though the chapter on danger is less persuading.

In spite of the editor, Smil’s own voice comes through highly, sceptical, sometimes curmudgeonly, setting out the realities, however susceptible to periodic break outs of scathing judgement (he truly dislikes SUVs!). Maybe he exaggerates the pessimism about the speed with which brand-new innovation can be presented, however his message about the scale and the wrenching effect of the shift we require to go through, to move far from our nonrenewable fuel source economy, is an important one.

.